Unit Author: K. Anne Pyburn, Indiana University

Representation

Learning Goals

Many people have had uncomfortable experiences in which someone talked about a group they belong to or something they have done in which the storyteller was trying to be accurate and had no idea anyone was being offended. In this exercise, students will practice representing each other in order to become more aware of their own behavior and more sensitive to the impact of representation.

Readings

"I'm Not the Indian You Had in Mind [5:28]" (2007)

“From Tonto to Tarzan: Stereotypes as Obstacles to Progress Toward a More Perfect Union.” Symposium at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, February 2017.

Activity and Lecture

Activity

Watch the 5:30 minute introductory remarks by Tiya Miles, then ask students to choose one of the four presentations in the Symposium Playlist by Gaurav Desai, Adrienne Keene, Imani Perry, and Jesse Wente.

The initial exercise shows how difficult it is to “represent” someone else. As the bulk of the class is about the pitfalls of representation, it is important to begin with the point that representation of someone or speaking on their behalf, even when you are trying to be positive and not embarrass them is extremely difficult. Students will learn to recognize patterns in strategies of representation that they can look for when they consider representations in other contexts.

Lecture

Students should choose or be assigned partners randomly and the partners should tell each other something about themselves that is personally slightly embarrassing – it should be small and nothing illegal! Usually these end up being about some bodily function that the person couldn't control in a social situation and people typically choose incidents from a time when they were very young, e.g. a 10-year-old musician who was stuck on stage with an orchestra for 4 hours after drinking a large soft drink was very glad his pants were black. It's actually good if the incidents are trivial. Each person will relate the story about their partner endeavoring to tell it in a sensitive way that is not embarrassing. If it is a large lecture class ask only some of the class to tell their partner’s story.

Discussion

Ask the class to note the consistency in the ways the stories are told. Summarize the strategies students used to allay embarrassment: euphemisms, laughter/joking, association with innocent naiveté of childhood, placed in context (unfair situation, misunderstanding), normalizing (phrases including: like everyone, or like myself, or like other nice people), note lack of volition or intentionality(in spite of her best efforts), etc. How might these strategies have negative consequences (disrespect, misinterpretation, stereotyping).

Representation Part 2

Background Information

Most people have some understanding of the problem of stereotyping, but very few realize how profound the influence can be or that all groups experience the negative impact of stereotyping to some extent. Claude Steele has done important empirical research on the effects of stereotyping and provides extensive data to back up his conclusions about how damaging stereotyping can be. His writing and presentations are very accessible and useful for teaching.

Readings

Steele, Claude. Whistling Vivaldi : How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Videos:

“Stereotype Threat: A Conversation with Claude Steele [8:18]”, from Not in our School. YouTube.

Activity and Lecture

Lecture

The instructor/lecturer should read the entirety of Whistling Vivaldi..., students should be given excerpts or asked to view online recordings of any of Steele’s public lectures.

Show these resources in class:

- Wikipedia. "Stereotypes of Indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States."

- Pinterest search of “Indian Halloween Costumes”

- "Native Americans Try On 'Indian' Halloween Costumes [2:30]" from As/Is. Posted 18 October 2015.

After each source, engage the class in a discussion of how the stereotypes of Native Americans that may appear to be trivial or even silly can threaten and impact people’s chances to succeed in the world.

Discussion

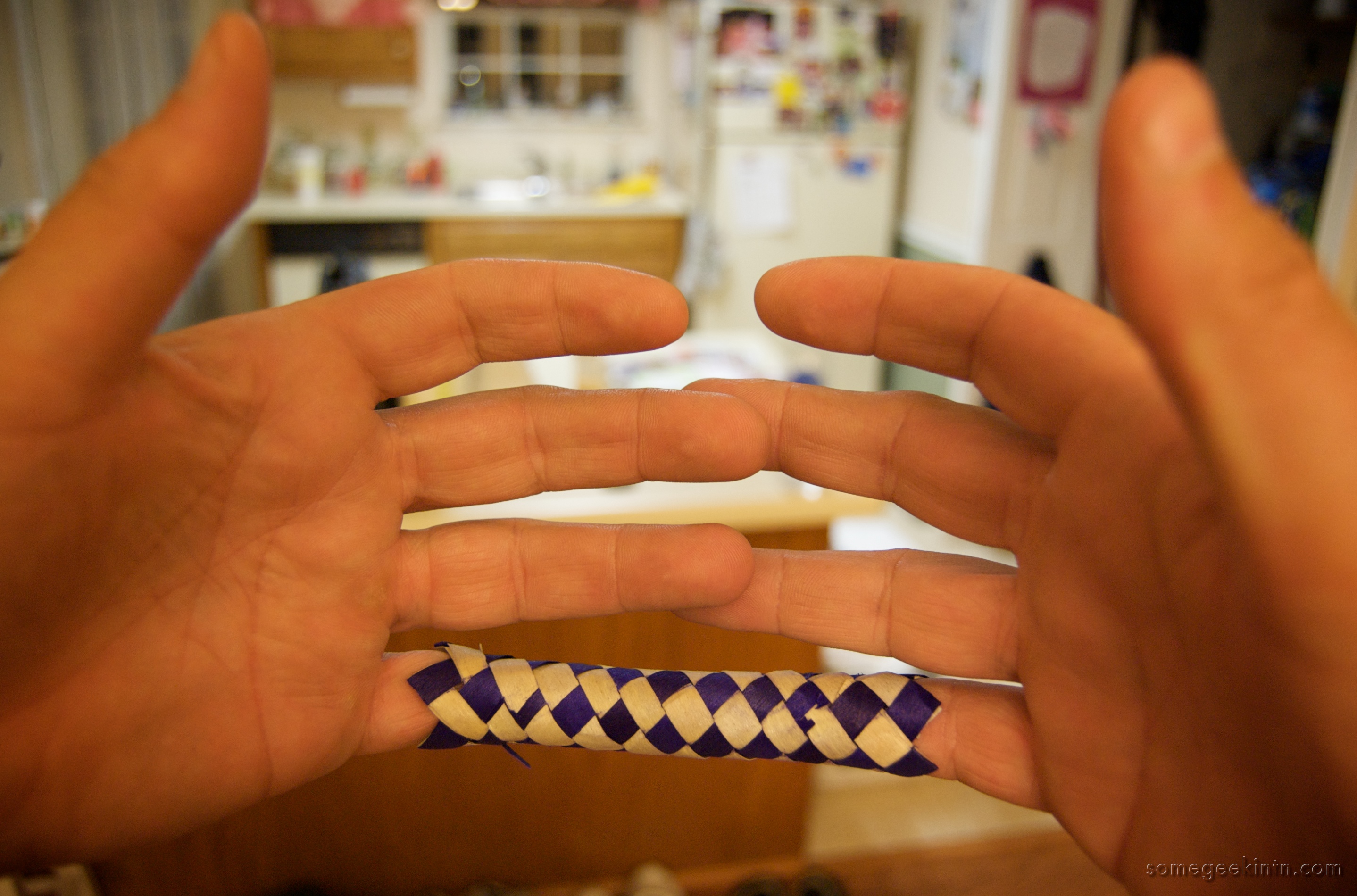

The political journalist Rebecca Traister described the phenomenon of the “finger trap” in which you are placed loosely within a joke (about Indians, or women, or some other social category in which you are counted as a member), that is so playful, so light—why protest? It’s only when you pull back—show that you’re hurt, or get angry, or try to argue that the joke is a lie, or, worse, deny that the joke is funny—that the joke tightens. If you object, you’re a censor. If you show pain, you’re a weakling.

Show the class a picture of a finger trap in case they haven’t seen one. Have the class come up with a few examples of the social phenomenon of the “finger trap” from their own experience or their imagination.

Discussion (small class) or brief in-class essay (large class). Can you respond to this type of real-world situation without being stereotyped by the storyteller? Give students 15 minutes to ponder this in class and ask some to share their conclusions. You can also do this in a small seminar by breaking the class into small conversation groups and having each report on the conclusions—of lack of conclusions—of their conversations.