Unit Author: Jayne-Leigh Thomas, Indiana University

Creating A New Partnership Under NAGPRA: Collaboration and Repatriation in the Alaskan Arctic

Learning Goals

- Understand the long-term nature of the NAGPRA process.

- Learn importance of communication and consultation, especially face-to-face.

- Understand the role of various gifting and other cultural traditions in positively working with different communities.

- Appreciate the importance of post-repatriation relationships and the continuing maintenance of those relationships.

Case Study

Introduction

Some experiences are meant to be private. Others are meant to be shared. Sometimes a story can be considered both. This is a story which has unintentionally reached national news in media outlets such as Indian Country Today (Russell 2015) and Newsweek. What these online versions don’t detail is the process and the hard work on behalf of both parties to develop a mutually beneficial partnership. This case takes a personal view of a recent repatriation between Indiana University and the Native Village of Barrow Iñupiat Traditional Government. It is a story of collaboration, commitment, and friendship and is intended not only to inform but also to educate, encourage, and promote similar opportunities and partnerships.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) is difficult. While the law is intended to be used as a guide or mechanism to promote successful relationship building and repatriation projects, this is rarely a straightforward process. Repatriation projects can be delayed or incomplete for a multitude of reasons. Some of those reasons include, but are not limited to, lack of availability of land for reburial, high rates of staff turnover in both tribes and museums, or waiting until summer when burial grounds are unfrozen. There can be disagreements, stalling tactics, and recalcitrance.

Despite difficulty and various complexities, NAGPRA projects with tribal communities have been some of the most rewarding and humbling experiences that I have ever had the opportunity to be a part of. Throughout the process, I have been fortunate to learn from people across the country, be invited to share their culture, and listen to their stories. And most importantly, with each project, the ancestors are finally returned home. I am honored to be a small part of that process.

This case study describes a repatriation that was efficient, fast, and immensely rewarding. I do not mention this to boast of the progress at Indiana, nowhere near so. We have an extremely long way to go, bridges to build, and partnerships to develop. But I offer it as an example of collaboration and partnership when two parties wholeheartedly work together to send the ancestors home.

Indiana University NAGPRA Project

In 1990, when NAGPRA was enacted, work began at Indiana University (IU) to inventory our extensive collections, which are at four repositories across campus. In accordance with the law, our inventory and summary information was submitted to the Departmental Consulting Archaeologist in the National Park Service Archaeological Assistance Division by the requisite dates of 1993 and 1995. After that time, consultation efforts were limited. Between 1993 and 2010, while inquiries were made, no claim for repatriation was submitted by any tribal nation. During this period, IU, like many collection holders, sent correspondence to tribal representatives; however, in cases in which no return contact was made, IU did not pursue consultation. Suffice it to say, things were complicated when I arrived, including insufficient record keeping, missed opportunities, inadequate communication, and decades of mutual mistrust. In 2010, when there was the change to the statute to require the return of culturally unidentifiable collections, the administration at IU realized they would need to reassess how to implement NAGPRA on campus—to comply with both the letter and spirit of the law.

The IU NAGPRA Project was established in 2013 with the full support of the Provost and the Office of the Vice Provost for Research. After being hired as the Director of the Project, I realized I needed to let people know things were going to change and that I was in it for the long haul. I wanted to establish a record of trust where none had existed. So, I decided that two of my most important tasks were to begin to understand exactly what was in our collections and to reach out to tribal communities with full intent to communicate. I embarked on large consultation trips across the country in 2014 to travel to tribal nations to meet with people face to face. These face-to-face meetings are such an important aspect of NAGPRA, but they are often neglected because of obvious hurdles to both tribes and institutions–money, geographical distance, and time. However, nothing can replace meeting with someone in person for laying a foundation for working together. Of utmost importance, I made sure tribes had my correct contact information, and I had theirs. I provided updated inventory and summary information, and I let them know of the new commitment to change practices at IU.

After reviewing our collections database, I realized that there were collections of human remains and associated funerary objects that could be culturally affiliated and could be repatriated quickly. One of these collections was listed as coming from Barrow, Alaska.

Utqiagvik (Barrow), Alaska

The Iñupiat people have been living at the northern edge of Alaska for generations. The Native Village of Barrow is located 350 miles north of the Arctic Circle and is the 14th northernmost village in the world.

IU’s collection of ancestral remains from Barrow had been acquired by Mollie Ward Greist and given to the University in the 1940s. Born in Monticello, Indiana in 1873, Mollie spent several years in Chicago training to become a nurse. Upon returning to Indiana, she married Dr. Henry Greist, and in 1921 she traveled to Barrow with her husband when he became a missionary and doctor for the Barrow community. They spent 17 years in Alaska and during their stay, Mollie collected thousands of objects, such as parkas and utilitarian items, which were sent back to Indiana. Today, the Mathers Ethnographic Collections at the Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology curate much of her ethnographic collection.

The book Under the North Star, which contains the edited manuscripts written by Mollie and Henry, describes members of the community taking Mollie to local burial grounds where bones and coffins lay on the ground (Taylor 2013). Mollie collected several mandibles and cranial fragments with the plan to give them to several dentists for study (Taylor 2013: 301).

I found that these human remains and others collected from Barrow were listed on the inventory of the IU Department of Anthropology.

Beginning Consultation

Consultation can take several forms–emails, phone calls, Skype calls; however, face-to-face consultation is best. NAGPRA is about creating a relationship, something that cannot be easily done through a faceless email or phone call. However, it would not be possible to fly to the North Slope of Alaska for a first meeting, so a starting phone call would be my initial step forward. The first phone call to a tribe can sometimes be awkward. You are calling to introduce yourself, explain why you are calling, and hoping it doesn’t sound like you are trying to sell something. There is also the hope that although people are perfectly entitled to their anger and frustration, no one yells at you despite the fact that it has been over 25 years since the law was passed and their ancestors still haven’t returned home.

Tribal communities have every right to be angry about the treatment of their ancestors. For years, the authority of science has been used as an excuse to perform analyzes on Native American remains without asking permission from tribes or even giving them an opportunity to offer their own research questions. Despite the law being over two decades old, thousands of Native American skeletons still lie in boxes in museum repositories throughout the United States.

For the remains from Barrow, two federally recognized tribes could potentially be affiliated, the Native Village of Barrow Traditional Iñupiat Government and the Iñupiat Community of the Arctic Slope (https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-11-17/pdf/2014-27152.pdf). After a couple of emails, I learned the person handling NAGPRA for both communities was Flossie Mongoyak. From the very beginning, Flossie received my calls and emails with understanding and optimism, and my fears abated. She was open to working with me on the repatriation process.

When Flossie asked me to escort the human remains and the associated funerary object within the collection to Barrow, I was both honored and terrified. I am not Native American, and I had not previously escorted ancestors home. My mind raced with questions and concerns. How would this work? Would I put the ancestors in my carry-on? Or in my suitcase in the baggage hold? Would Flossie be mad at me for even asking such a question, even though the question was a matter of necessity? How would I get through security? Would the collection need to be x-rayed? Would that be ok with Flossie, as the representative of the tribe? What about preparations should I make for the ancestors on behalf of the tribe? What would the tribe even want? Would it be considered offensive if I asked?

Over the next few months, our communication increased and plans took shape. One topic of discussion was financial logistics. Who would pay for the reburial? Both IU and the Native Village of Barrow would have financial responsibilities, with travel expenses on my part, and reburial costs in Barrow. I suggested applying for a National Park Service NAGPRA Grant, something neither IU nor the Native Village of Barrow had ever attempted to obtain. We decided that the best route would be for me to write the grant application and the tribe would put their name on it, and if received, two-thirds of the grant would go to the tribe, with the remaining money going to my travel expenses to get to Alaska. We submitted the grant for review in 2014.

This collaboration was a win-win situation for both parties. Several months later, in 2014, we received news that our grant proposal had been successful, covering the costs for both the tribe and IU. We had also posted the Notice of Inventory Completion document on the Federal Register. After thirty days, IU would transfer control to the Native Village of Barrow Iñupiat Traditional Government and move forward with the repatriation once an official claim had been received.

Flossie suggested I wait to bring the remains to Alaska until June 2015 when the annual Nalukataq (whaling festival) celebrations would be held. That way, I could partake in the festivities with the tribe. It thrilled me to be invited to share such an important event. But this brought more questions. Was there a gift I could bring to share with the community? What should I wear? Flossie laughed. Wear winter clothes–at the Top of the World, although the sun wouldn’t be setting at that time of year, it was still going to be cold.

In terms of a gift, I had originally very naively thought that perhaps chocolates or bags of Indiana popcorn could be handed out. Flossie had a better idea—citrus fruit. Fruit is extremely expensive in Barrow, especially citrus fruits. But what kind were we talking about? Pineapples? Limes? Mangoes? Flossie felt oranges would be a better choice: a bottle of orange juice cost $18 at her local store. Rather than having the oranges shipped, and worrying about whether they would arrive exactly in time for when we needed them on the days of the Nalukataq, I filled a plastic tote with oranges and carry it with me as extra luggage.

Another thing to coordinate was the date of my flights: I had to schedule the repatriation trip around the whaling festival and the return of the whales. Starting in the winter, bowhead whales begin their annual migration up the Bering Strait towards the Chukchi Sea and the Arctic Ocean. The whales arrive near Barrow during the months of April and May. The number of successful whale harvests depends on the number of days for Nalukataq, and we would need to wait until the whales came in before festival dates in June could be set.

I’ll never forget Flossie’s phone call at the end of April, letting me know the whales had arrived and the festival dates had been set for the end of June. Countdown had begun. Dr. April Sievert, director of the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology, was invited on the trip to Barrow as well and, with less than a month to go, we began frantically looking for flights. For April, as a relatively new director of a large collections repository with thousands of items to be repatriated, this trip would provide a matchless and humbling experience in learning NAGPRA.

As the date of our flight to Barrow became closer, we started preparing for the repatriation. The ancestors were wrapped separately in organic cotton muslin, per Flossie’s request, and placed into a box which would go in my carry-on suitcase. April and I went to the grocery store one afternoon and cleared out the store’s entire selection of clementines, layering them in a tote with sheets of foam in between. The entire container held two hundred and ninety-nine clementines.

The tribe asked us to bring cotton batting, which would be used to wrap the ancestors during the reburial. My experience in trying to ship this directly to Barrow underscored how difficult it is for their isolated community to receive supplies. The package went from Bloomington to Anchorage to Barrow, back to Anchorage, to Iowa City, to Cincinnati, then ultimately back to Bloomington over a span of six weeks. I wasn’t attempting UPS again, so the cotton batting was squeezed into our luggage. Arrangements were made with the chief of TSA security in Indianapolis so that although I would have to go through the x-ray machine, the ancestors would not be required to. Flowers, to be placed in the grave during the reburial, were ordered to be shipped up from Anchorage. We were ready.

Traveling to Barrow

When April came to pick me up at 3am on June 23rd, it was 84 degrees with 85% humidity and I was wearing a snow jacket. The ancestors were safely secured in my carry-on suitcase which I would have with me at all times on the journey. Two months prior, I had traveled for the first time with ancestors and was feeling marginally better about having that first experience completed. There was a slight problem with TSA security in Indianapolis, as they would not let me go around security as I had done two months before. Although I had arranged everything with the TSA security director, they couldn’t reach him on the phone and since he wasn’t working and wasn’t available, they didn’t care what I had previously arranged, the ancestors and I were going through security, or I wasn’t getting on the plane!

Flossie and I had previously spoken about if such a situation was to occur and how I would handle it. While Flossie did not wish for the ancestors to be x-rayed, she understood that it might have to happen in order for me to get through security and she trusted the decisions I would make. I remember taking a deep breath, wondering if I was going to make a huge mistake, but decided that the ancestors and I would be x-rayed in order to pass through security.

Indianapolis to Chicago to Anchorage to Prudhoe Bay to Barrow. Five airports, nearly 24 hours to the top of the world. There are no roads in and out of Barrow, so the flight was full, carrying passengers who had flown to Anchorage that morning for doctor’s appointments or people who had gone to the oil fields in Prudhoe Bay.

The airport in Utqigvik is extremely small. We got off the plane with the ancestors on the runway and walked into the terminal, a long metal building full of people meeting relatives and waiting for containers shipped up from Anchorage. Thankfully, all of our luggage arrived, including the oranges which were remarkably unsquashed. The next morning, after sixteen months of phone calls and emails, I finally got to meet Flossie in person.

The next few days consisted of tours of the village, walking the beach along the Arctic Ocean, and discussing the reburial. The tribe was waiting on the return of additional ancestors from other museums, and while the actual reburial would not occur while we were in Barrow, April and I were taken out to the cemetery to help select the burial plot for the ancestors. The Native Village of Barrow had completed a repatriation the year prior, reburying remains which had been returned by the U.S. Navy. The plot where those ancestors were laid to rest was marked by a cross and enclosed by a white picket fence. The plot we selected was adjacent to this plot, and would also be marked in the same fashion, with a plaque on the cross, letting community members know that their ancestors had been returned and which institution had finally returned them.

Nalukataq

Nalukataq means ‘to toss up’ (F. Mongoyak, personal communication, 2015). It is the summer whaling festival held to celebrate the spring’s successful whaling harvest. Characterized by the Eskimo blanket toss, where members of the community are tossed into the air from a stretched seal skin blanket, the Nalukataq also includes several days of feasting and Eskimo dancing, which lasts until after midnight.

A Nalukataq is all about community. Most offices throughout the village are closed on each day so that the entire community can partake in the event. The Nalukataq would be held in the gravel lot along the beach next to our hotel. There were nine successful whaling teams in 2015 and the distribution of whale meat would be held during three days of feasting and celebration.

Each whaling team can comprise 10 men that go out to harvest the whale; however, the women make the umiaq or skin boats made of stretched seal skin and sew the garments made by the whalers. On the day of Nalukataq, each whaling team wears elaborately sewn coats, with their specific team colors and logos embroidered on the back.

The first morning of Nalukataq, we watched from our hotel as the horseshoe shaped arena was built with wood and sheets of plastic, dozens of families arriving to set up chairs and coolers along the edge of the arena to reserve their spot. Tables were arranged in long rows down the center of the open arena and above, the flags representing each successful whaling team flapped in the Arctic breeze. The Nalukataq officially begins at noon with words from one of the Whaling Captains, then there is the selection of an Elder to intercede for the harvest with a prayer. Then the members of the whaling teams walk around the arena, handing out rolls and pouring cups of hot tea. After soup, comes the chunks of frozen whale meat, boiled whale intestines, and Eskimo donuts. This is then followed by mikiyaq, raw, fermented, bloody whale meat, then maktak. Maktak is the soft pink blubber and black skin of the whale that is cut into small slices with an ulu. Originally a woman’s knife, ulus are now used by both men and women in the community. The fins of the whale are brought in on pallets behind trucks and only honored guests are invited to come and cut strips off the fin. I was allowed to cut a large slice off of one of the fins, but then gave it to Flossie, who said she would send it to her Yupik relatives in southern Alaska.

Feasting lasts for eight hours each day. Bags of oranges and apples which had been donated by the oil companies and our container of clementines were brought out and distributed to children and the elderly (Figure 2).

Throughout the festival, members of the community would get up and say a prayer, wish a family member Happy Birthday, or sing a traditional song. April and I sat with Flossie’s family and tried everything that was offered to us. I will never forget the frozen chunks of arctic char caviar which melted between my fingers, the sour smell of the fermented whale blood that I licked off my fingers, and how excited we were to try the bright orange salmonberry pie.

After all the whale meat had been distributed, the blanket toss begins. Members of the community gather around the edge of a seal-skin blanket which is erected high above the arena ground and together, they toss someone standing on the blanket high into the air, the midnight sun reflecting brightly off the ice in the sea. After the blanket toss, everyone heads to the high school gym for the Eskimo dance. Consisting of traditional dancing, drumming, and singing, the Eskimo dance can last until two or three in the morning.

Heading Home

Before we left for Indiana, I gave Flossie a book showing pictures of the IU Bloomington campus. In several pictures, there were images of autumn leaves, trees in Dunn Meadow changing to reds and golds. She lingered on those pages, saying she had never seen those leaves and how she wished she could see them, and that once in a dream, she had gotten to see them. I realized then how much I take things like that for granted. We complain about the leaves, kicking them as we walk down the street and stuff them into bags or leave them to rot. There are no trees in the tundra around Barrow. Aside from one pine tree in Barrow, the ‘trees’ are made from strips of baleen. I then made Flossie a promise that somehow, we would get her to Indiana to see the leaves and so that we could return the hospitality the tribe had so graciously shared with us.

After 10 days in Barrow, I was sad to leave the small Eskimo village at the top of the world, but simultaneously happy. I had met new people, shared in the wonderful Nalukataq celebrations, and finally, the ancestors were back where they belonged.

Moving Forward

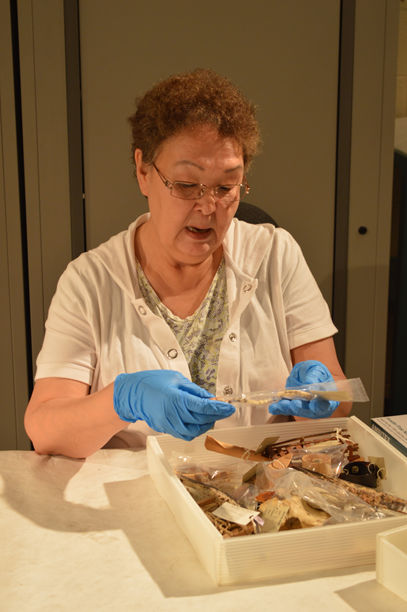

Communications between Flossie and me continued over the next year and, as promised, I was able to arrange for her to come to Indiana. On October 16, 2016, she flew from Utqiagvik to Indianapolis, the longest trip of her life and first trip east of the Mississippi River. The purpose of her trip was to come and look at the Greist collection, which was curated by the Mathers Museum of World Cultures (Now IU Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology). While primarily comprising utilitarian objects such as fishhooks and spoons, the collection might also contain sacred objects or objects of cultural patrimony, which would be repatriatable under the law. Flossie, as the tribal expert, needed to view the objects to make those determinations.

Over a span of several days, with help from the Mathers staff, Flossie was able to view artifacts from Barrow, which had not been seen by someone from that community in nearly 100 years (Figure 3).

She took hundreds of photos, assigned Iñupiat names to items in the collection, and was able to provide accurate identification on incorrectly labeled artifacts.

The rest of the week, Flossie met with students, provided a lecture at the First Nations Educational and Cultural Center, and experienced Indiana and Midwestern culture. We drove up and down the roads of Bloomington and the surrounding areas, Flossie videotaping and taking pictures of the changing leaves to share with her family.

Conclusion

Today, I write this account with Flossie's permission, support, and advice. We have both discussed how strange are the circumstances that have brought us to becoming such good friends. We have plans for new collaborative projects, with her possibly returning to Indiana and myself visiting Barrow. I consider myself extremely lucky to have had this experience and to have become such close friends with Flossie. I was positively surprised and impressed at several points about Flossie’s willingness to work through the process with me and include me in the tribal processes. One lesson for consultation is to be open to the responses from tribes instead of assuming you'll know how they will respond. Successful repatriation doesn't end with the ancestors' being returned to the ground, but is successful when all parties have long-term relationships.

It is a shame that in some archaeological circles, NAGPRA is considered a hindrance or a nuisance. Thankfully, that opinion, for the most part, seems to be fading within the archaeological field. It may be a generational difference, with new graduates realizing the potential opportunities and partnerships that can be obtained by working with indigenous populations.

References

Russell, S. (2015). "NAGPRA Bears Fruit! IU Anthropologists Return Remains, Attend Nalukataq."Indian Country Media Network (Oct. 16, 2015). Also published as "Human Bodies Vs. Data: Doing the Right Thing With Native Remains."Newsweek (Oct. 17, 2016).

Taylor, S. U. (2013). Under the North Star, White County Edition. Monticello, Indiana: White County Historical Society.

Discussion Questions

- What dilemmas did Jayne-Leigh face? What dilemmas did Flossie encounter?

- What was at stake for each party?

- How did they overcome these, individually and together?

- What efforts did the people and institutions involved make to facilitate respect and positive outcomes?

- Jayne-Leigh was surprised at several points about the willingness of Flossie to work through the process with her and include her in the tribal processes. What did each woman gain through their work together?

- What roles do conflict, reconciliation, and collaboration play in this case study?